How Long Does It Take To Cross the Atlantic Ocean By Boat? (Cruise ...

Atlantic crossings are one of the most popular topics I'm regularly asked about. How long does it take to cross the Atlantic Ocean? Is it safe to complete an ocean crossing on a small boat? What time of year are best time to cross such a giant expanse? Do you worry about bad weather? Does it take a long time? Do you need to be an experienced sailor to complete such a voyage? In this lesson, I will shed light on these questions and many more.

Index

- Background Information

- Standard Crossing Times

- History of Atlantic Crossings

- Famous TransAtlantic Voyages

- Modern Day Crossing Records

- Factors to Consider Before Crossing

- Further Reading

- References

Background Information

An Atlantic Oceanic crossing encompasses roughly 2800 to over 3000 nautical miles. They originate and terminate from virtually anywhere coastal, but on the Western side it is common to depart from either New York or Florida if the voyage is through the United States (commercial ships leave from any large port). On the European side, a good place to commence or depart from is the Iberian Peninsula (Spain or Portugal) or U.K.

An important thing to consider while reading this article: the listed numbers refer to days in open seas and navigating and do not counting rest stops at safe havens.

Standard Crossing Times

One of the main reasons modern ships take longer to cross are fuel consumption exponentially increases at higher speeds. Once back near land, they are able to travel at faster speeds. For this reasons none of these vessels can compete to records set by more efficient racing boats.

Yachts

- My first Atlantic Crossing took roughly fourteen days to complete. Most Superyachts take nine to fourteen days to cross. Yachts typically tend to cross at slower cruising speeds of 8 - 15kts. For more information on what defines a yacht, see our previous lesson.

Cruise Ships

- Modern day cruise ships take roughly six to eight days to cross. Cruises tend to navigate at 20 - 25kts for crossings. Cruise ships not only offer an exceptional speed for passengers, but also offer large upper decks and guest spaces for those aboard.

Saling Vessels

- Sailing vessels and sailing yachts take roughly three to four weeks to perform an Atlantic Crossing. Depending on weather conditions, they can average 4 - 8 kts during the passage.

Cargo & Commercial Ships

- A Cargo ship or commercial ship can take ten to twenty days to complete the passage cruising at 12 - 20kts. However, the difference with these vessels is that container ships run all year round and can encounter monstrous weather conditions while luxury cruises and yachts defer passage until proper seasons for passenger comfort. Freighter cruises, an unorthodox was to travel as a passenger on a cargo ship, allow you to experience a more raw seagoing experience.

History of Atlantic Crossings

In order to better appreciate modern crossing timelines, it is worth examining the history of Atlantic Crossings. Who completed the transatlantic crossing for the first time in history? Did all early explorers brave the open ocean with primitive technology?

Vikings

Contrary to popular belief, modern day scientists have attributed the Vikings' longship as the first transatlantic sailing ship to land upon the New World. During the Viking Age (793 - 1066 AD), the Scandinavians reached the American continent from their port of departure in Northern Europe. New information has attributed this arrival in Canada to 1021 A.D. (471 years before Columbus)![1] Aboard their special type of boat, a long and narrow wooden vessel that while traveling in good conditions could sail at an average speed of 8 knots. Viking navigation relied mostly on coastal landmarks, wind patterns, animal migratory patterns, expert maritime knowledge of tide and weather as well as tools called sunstones, an ancient predecessor to the compass.[2]

Even with all of these methods of navigation and a sturdy boat, the Viking voyages were highly affected by weather. The trip from Sweden across the English Channel to the United Kingdom ranged between 3-6 days and up to a few weeks depending on conditions.[3] Due to their method of sailing along the coast and traveling in smaller legs, adverse wind or heavy weather could delay sailors at a destination while awaiting good weather conditions for days or several weeks. This meant Viking seamen could reach Greenland from Norway in 3-4 weeks.[4] Lastly, the trip from Greenland to Canada across the North Atlantic spanned another 1600 nautical miles and could be completed in two to six weeks! Upon reaching their destination of Vinland (L'Anse aux Meadows),[5] Erik the Red and his explorers could have reached a totaled travel time of five to ten weeks (over two months)!

Finn Bjørklid, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Spanish

In the most famous Atlantic Crossing, Genovese navigator Christopher Columbus (Christophorus Columbus) sailed from Spain to the American continent aboard the Santa Maria along with the smaller Nina and Pinta. His goal was to bring back good news to Spain revealing a direct western route to India. Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera, Spain on 3 August 1492 and stopped at the Canary Islands, a small set of islands that belong to Spain off the eastern coast of Africa for repairs. It was not until much later that he reached the West Indies on the 12th of October, 1492. This totaled 71 days of sailing from Europe until his destination in the Caribbean.[6] During his return trip through the Portuguese Azores Columbus' men travelled slightly faster, taking 62 days to complete the voyage.[7] Lying far off the Portuguese coast, these islands served as safe haven to replenish supplies and complete repairs. However, this length of time barely showed any improvement; only the worst Viking voyages spanned so much time.

Phirosiberia, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It was during his second voyage that Columbus reached the Windward Islands in just over 40 days (barely over a month).[8] During the third voyage, his fleet traveled through Cape Verde using the southern route in 31 days.[9][10] Cross ocean voyages spanning nearly 3000 nautical miles were completed even faster than prior Viking voyages of less than 2000 nautical miles.[11]

English

Much later in 1609, Henry Hudson sailed across the Arctic Circle in hopes of discovering the Northeast Passage connecting the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean. Despite searching for years, he never reached his final destination. However, his discovery of the Hudson Bay and other explorations of the NE US helped propel forward Dutch colonialism and settlements across the NY area.[12]

Chinese

Aside from these well known explorers, there are also claims regarding other nations reaching the Americas. It is long-term belief that Chinese explorers visited the United States and South America in the early 1400s. The discovery of a map of the two American continents by early Chinese sailors pre-date Columbus' voyage by nearly 75 years.[13]

Welsh

However, there are other accounts of even earlier visitors to America that haven't been verified yet. According to a Welsh poem, Prince Madoc of Wales sailed to America in 1170 with the right crew to help him escape from Wales as his brother usurped the throne. They arrived in Mobile Bay, Alabama where they settled and intermixed with the Native Americans.[14] The legend is only supported by other anecdotal accounts of Welsh forts and ruins left behind, tales of blonde hair and blue eyed Native American tribesman, and a story regarding a Welshman freed by Natives upon using the Welsh language. Even Thomas Jefferson believed the accounts and instructed Lewis and Clarke to search for these Welsh Indians.

Scottish

Another pre-Columbian trip to the Americas is found in the Scottish legend of Henry Sinclair, 1st Earl of Orkney. After conquering the Northern Isles, the Earl saved the lives of two shipwrecked Venetian brothers. After hearing stories of those marooned at sea and "reaching distant lands in the west," Sinclair embarked on a journey out west with a fleet of ships, his two rescued companions as crew members. This tale is more believable because Nordic knowledge of Newfoundland was already widespread and Henry's crew followed the same path. Similarly, the Mimac tribe of Nova Scotia tells a traditional story that corroborates the 1398 trip claimed by Sinclair. There are also artifacts left in Westford, Massachusetts that also allude to the expedition.[15]

Famous Transatlantic Cruises

Steamship Great Western

With the onset of each new naval technology, humankind continued to test newer ships at an Atlantic Crossing. During the early 1800s a new type of vessel, the steamship became commonplace. The steamship succeeded the steam boat as a larger vessel capable of revolutionizing international travel, trade and globalization. Without a dependence on wind, new trade routes previously inaccessible during improper conditions. Up until this point, ships could only cross in three to four weeks.[16]

1838 served as the inauguration of the first steamship built for the purpose of an Atlantic Crossing. This wooden passenger vessel ranked the largest in the world from 1837-1839 and completed this route for 8 years. The SS Great Western averaged 16 days, 0 hours (7.95 knots) westward to New York and 13 days, 9 hours (9.55 knots) during the journey home.[17]

Queen Mary & Queen Mary II

The late 19th century brought the onset of the modern ocean liner, complete with luxurious cabins, dining, and deck spaces for passengers. These large ocean liners were mainly constructed by Germany and the United Kingdom as bigger boats that carried thousands of passengers across the Atlantic Ocean. The main routes for these first steamships to cross with such a large passenger count depended upon their destinations. Ships bound for the Southern Hemisphere took the Southern Passage, whereas cruise lines with ports of call like New York City and the US East Coast remained in the Northern Hemisphere while crossing the Atlantic East.[18]

The RMS Queen Mary is a retired British liner that served in operation from 1936 to 1967. She sailed as one of the first liners on her maiden voyage on May 27th, 1936, and even served as a troopship carrying Allied soldiers during WWII.[19] Queen Mary made her fastest ever crossing, returning to Southampton in only three days, 22 hours and 42 minutes at an average speed of nearly 32 knots (59 km/h). Her successor, the Queen Mary II is the last ocean liner in service (as opposed to modern day cruise liners). She averaged 7 days to cross the Atlantic Ocean and her maiden voyage from Southampton, UK to Fort Lauderdale, FL took 14 days to complete.[20]

Modern Day Crossing Records

Sailing

Crewed

- Fastest Monohull - Sailing Superyacht Comanche - 5 days, 14 hours, 21 minutes and 25 seconds,

Avg. Speed: 21.44 knots (39.71 km/h)[21] - Fastest Multihull - Sailing Trimeran Banque Populaire V - 3 days 15 hours 25 minutes 48 seconds,

Avg. Speed: 33.41 knots (61.88 km/h)[22]

Single-Handed

- Thomas Coville - Sailing Trimeran Sodebo Ultim - 4d 11h 10m 23s, Avg. Speed: 28.35 knots (52.50 km/h)[23]

Power

- Time of the Fastest Atlantic Crossing (1992) - Aga Khan's 220' Jet engine powered boat Destriero - 2 days, 10 hours and 54 minutes, Avg. Speed: 53 kts[24]

- Former Record Holder (1989) - Tom Gentry's 110' Powerboat Gentry Eagle - 2 days, 14 hours 7 minutes,

Avg. Speed of 47.4 kts (54.5 mph)[25] - Fastest Atlantic Passenger Ship/Hales Trophy Holder (1952) - SS United States - 3 days, 10 hours and 40 minutes, Avg. Speed: Just over 35 kts[26]

- Inventor of Virgin Atlantic Challenge Trophy (1987) - Richard Branson's Virgin Atlantic Challenger II - 3 days, 8 hours and 31 minutes, Avg. Speed: Just under 36kts

Notable Vessels

- Smallest Powerboat to Cross the Atlantic, First Flats Boat to Cross the Atlantic, Longest Ocean Voyage in a Flats Boat (2009) - Ralph Brown 21' Flats Boat Intruder 21 - 1 month[27]

- Inflatable Zodiac (1952) - Alain Bombard's L'Hérétique crossed the Atlantic from East to West - 113 days[28]

- Raft of wood and Rope (1956) - Henri Beaudout's L’Égaré II, crossed the Atlantic from West to East, from Halifax to Falmouth - in 88 days[29]

- Rowing (2005) - Vivaldi Atlantic 4 - 39 days

- First Recorded Non-Stop Transatlantic Kayak Crossing (2010) - Sexagenarian Aleksander Doba - Dakar, Senegal to Brazil in 99 days later[30]

- Smallest Sailboat to Cross the Atlantic (1993) - Hugo Vihlen's Father's Day measuring 5ft 4 inches - 105 days.[31]

Factors to Consider

When planning a long passage, it is a good idea to consider the following factors in the Passage Plan. I will include additional information about passage planning at a later date, but here is a quick overview of what a seasoned mariner would consider for these crossings.

Winds

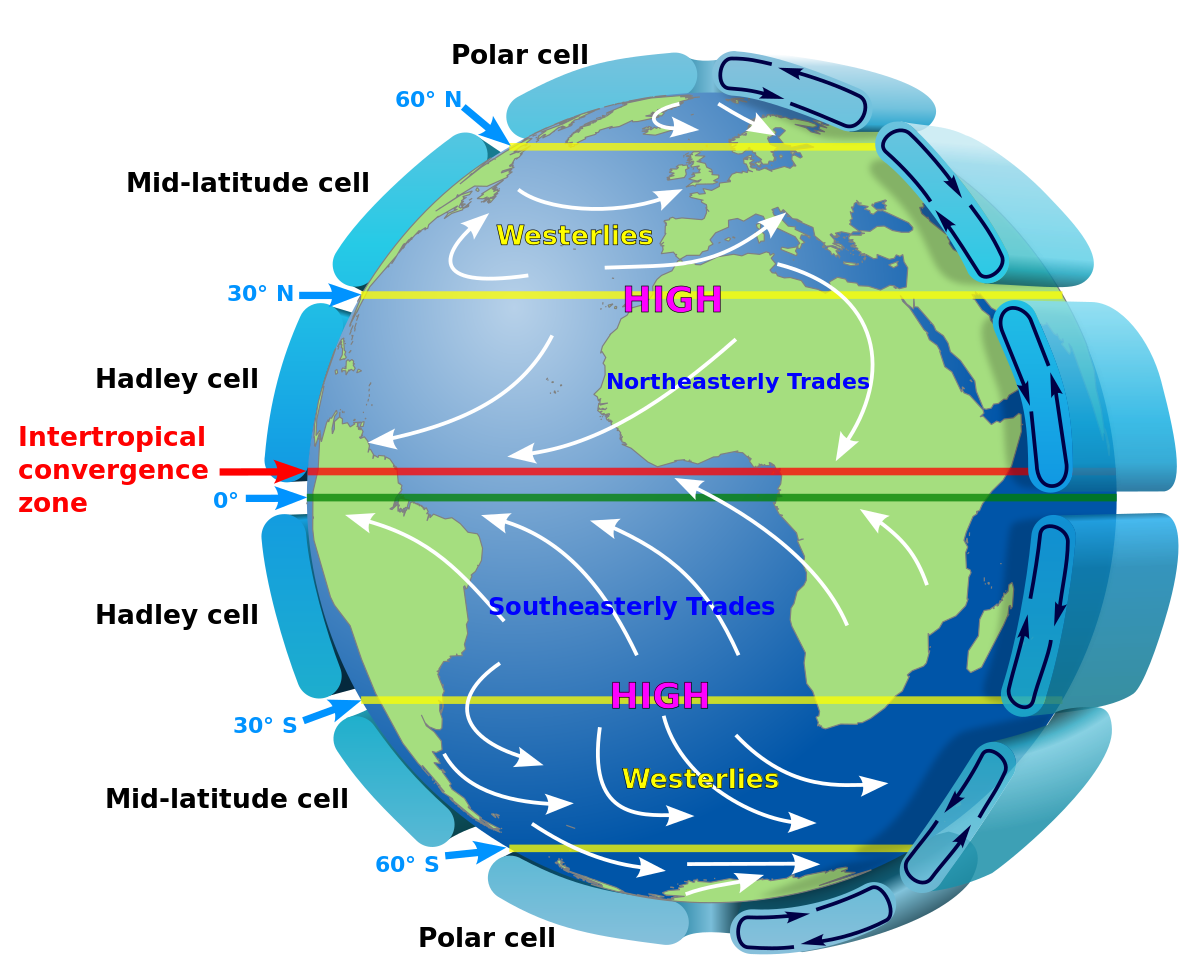

Due to the Earth's rotation, winds moving across the surface of the planet are subject to Coriolis Effect and experience deflection as they move north and south. This creates areas of Trade Winds, Westerly Winds, high winds, and also zones devoid of any wind. Although mostly essential for sailboats, an understanding of these concepts also help motor yachts. Similarly, understanding the Azores high pressure system and how it brings winds from the western Sahara into the Atlantic can help predict future localized weather.

Kaidor, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link via Wikimedia Commons

Ocean Currents

There is a large offshore ocean current originating in the Gulf of Mexico at the southern tip of Florida and following the US East Coast before crossing the Atlantic towards Europe. This current, known as the Gulf Stream, can shift offshore by a few miles at a time and also changes speed throughout the year. Utilizing this current (or avoiding) while traveling along its path can help a vessel shave time off their passage.[32]

Seasonal Weather Patterns

A good thing for mariners to weigh when deciding on departure dates are the seasonality of the Atlantic Ocean. Vessels should avoid traveling the southern Atlantic during Hurricane Season (June 1 - Nov. 30) in order to avoid dangers from Hurricanes and Tropical Storms. Similarly, the North Atlantic is home to terribly harsh seas in winter months. November to May tend to be the best months but local maritime guides should be analyzed to pick the best window when examining ocean passages, especially during these seasons. Regular weather reporting must be maintained during the voyage as well for sudden changes.

Boat Size

Although prior records show that you can sail the Atlantic on virtually any sized vessel, there is a consensus that a yacht of 30ft or larger is standard for this journey. Smaller boats can surely be used, but in order to maintain a level of comfort and safety then 30-40ft should be the minimum.

Total Distance of this Journey

As I mentioned earlier, the average distance for an Atlantic crossing can 2800 nautical miles, but a greater distance of over 3000 miles is possible depending on endpoints. One way minimize fuel consumption on this voyage is analyzing the differences between Straight Line (Rhumb Line) and Great Circle Navigation. In the simplest terms, because the Earth is a curved shape the fastest route between two locations is a curved line when drawn on a flat map. The great circle is the curved line we see on our chart but is actually the straightest path in real life. The rhumb line you draw on a map is actually a curved path in real life. Understanding this concept can save you up to 10% of your travel time.

Jacobolus, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Refuge Ports

The first thing a seaman must consider is how much fuel will the vessel need. A common rule of thumb is to carry 1.5x the amount you'll need for the voyage. Similarly, carrying enough spare parts for the trip is essential. However, vessels can also perform stopovers along the voyage in Bermuda, the Azores, Canary Islands and Cape Verde. By shrinking the travel time into smaller runs a boat can stop for refueling or resupplying after an arduous journey.

Hopefully this answers all of your queries regarding an Atlantic Crossing and leaves you with an aching desire to travel the seas yourself! No matter what type of vessel you transit the Atlantic aboard, be prepared to spend a lot of time with your crew! For more information on the various crew members onboard a superyacht, see our previous lesson. If so, please contact us and we'll help you start your first crossing aboard a beautiful Superyacht!

Further Reading

- Freighter Cruises

- Goodbye Columbus, Vikings Crossed the Atlantic 1000 Years Ago

- How did the Vikings Cross the Atlantic?

- Menzies, G., & Vance, S. (2009). 1421: The year China discovered America. Playaway Digital Audio

- Mystery of Mandanas Indians - Welsh Indians?

- Prince Madoc in Alabama

- Cunard's Queen Mary

- Jimmy Cornell

- Titanic II to Set Sail

- Ancient Ship Sail Speed

- Video of Container Ship In Extreme Weather Crossing the Atlantic

References

-

Dunham, W. (2021, October 20). Goodbye, Columbus: Vikings crossed the Atlantic 1,000 years ago. Reuters. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/science/goodbye-columbus-vikings-crossed-atlantic-1000-years-ago-2021-10-20/

-

Metcalfe, T. (2018, April 12). How human error led the Vikings to Canada. LiveScience. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.livescience.com/62284-how-vikings-reached-canada.html

-

Wade, D. (2022). How long did it take the Vikings to sail to England?: Life of sailing. RSS. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.lifeofsailing.com/post/how-long-did-it-take-the-vikings-to-sail-to-england

-

Metcalfe, T. (2018, April 12). How human error led the Vikings to Canada. LiveScience. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.livescience.com/62284-how-vikings-reached-canada.html

-

Bjørklid, F. (2022, September 10). Map of the Greenland-Vinland Voyage. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.worldhistory.org/image/9190/map-of-the-greenland-vinland-voyage/

-

Dyson, J., Christopher, P., & Miguel Coin Cuenca Luís. (1991). Columbus--for gold, god, and glory. Madison Press Books.

-

Lehrman, G. (n.d.). The Gilder Lehrman Institute of american history. Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/columbus-reports-his-first-voyage-1493

-

Bedini, S. A. (1992). The Christopher Columbus encyclopedia. Macmillan Press Ltd.

-

Saunders, N. J. (2005). Peoples of the Caribbean: An encyclopedia of archeology and traditional culture (p. 75-76). ABC-CLIO.

-

Jane, F. V. I. (n.d.). In The imaginative landscape of Christopher Columbus (p. 158). Princeton University Press.

-

Hester, J. L. (2018, April 30). Why can't we figure out how the Vikings crossed the Atlantic? Atlas Obscura. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-did-vikings-cross-the-ocean

-

Laet, J. de. (1630). In Nieuvve Wereldt Ofte Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien (p. 83). essay, Elsevier.

-

Whipps, H. (2006, February 6). Map fuels debate: Did Chinese sail to New World First? LiveScience. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.livescience.com/7002-map-fuels-debate-chinese-sail-world.html

-

Johnson, B. (n.d.). The discovery of America - by the welsh prince madog in the 12th century. Historic UK. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/The-discovery-of-America-by-Welsh-Prince/

-

Undiscovered Scotland. (n.d.). Undiscovered Scotland. Henry Sinclair, 1st Earl of Orkney: Biography on Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/usbiography/s/henrysinclair.html

-

Pascali, L. (2017). Globalisation and Economic Development: A Lesson from History. The Long Run. Economic History Society. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- Gibbs, Charles Robert Vernon (1957). Passenger Liners of the Western Ocean: A Record of Atlantic Steam and Motor Passenger Vessels from 1838 to the Present Day. John De Graff. pp. 41–45. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

-

Frame, C. (2022). Ocean liners. Ocean Liners vs Cruise Ships | Chris Frame's Cunard Page: Cunard Line History, Facts, News. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from http://chriscunard.com/history-fleet/translantic-liner/

-

Travel, T. (2016, August 22). Remarkable things you didn't know about the ocean liner queen mary. The Telegraph. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/cruises/articles/fascinating-facts-about-queen-mary-cruise-ship/

-

Press, A. (2004, January 26). Queen mary 2 goes on Maiden Voyage. CBS News. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/queen-mary-2-goes-on-maiden-voyage/

-

International, B. (n.d.). 3 speed records smashed by Comanche. The speed awards already broken by Comanche. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.boatinternational.com/yachts/news/speed-records-already-smashed-by-comanche--26961

-

Administrator. (2011). Transatlantic, Ambrose Light Tower to lizard point, crewed. Construction. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.sailspeedrecords.com/transatlantic-crewed

-

Penfornis, Y. (n.d.). Lauching of Thomas Coville's Sodebo Ultim' trimaran. Launching of Thomas Coville's Sodebo Ultim' trimaran. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from http://www.multiplast.eu/en/news/newsletters/composite-yacht-news/713-launching-of-thomas-coville-s-sodebo-ultim-trimaran.html

-

Springer, B. (2016, February 1). British team sets sights on transatlantic powerboat speed record. Forbes. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/billspringer/2016/01/31/speed-is-sexy-and-records-are-meant-to-be-broken/?sh=1b9905326e42

- Pickthall, B. (1989, July 28). Eagle wings its way to a transatlantic record. The Times. Dave Sansted. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- Beeston, Nicolas. (1986, June 30). Branson captures Blue Riband-Virgin Challenger Atlantic crossing. The Times. Retrieved 3 August 2017

-

Services, M. (2009). Brown Brothers Complete Atlantic crossing - US to Germany. Sail World - The world's largest sailing news network. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.sail-world.com/Australia/Brown-Brothers-complete-Atlantic-crossing-US-to-Germany/-61443?source=google

- Bombard, A. (1953). The Voyage of the Heretique. Simon and Schuster.

-

Wadden, M. (2012, August 3). Three Canadians, two kittens, one raft: A little-known journey across the Atlantic. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/three-canadians-two-kittens-one-raft-a-little-known-journey-across-the-atlantic/article4462515/

-

Garling, C. (2011, February 10). 64-year-old kayaker completes trans-atlantic voyage. Wired. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.wired.com/playbook/2011/02/epic-kayak-guy/

-

Stickland, K. (2022, May 26). Crazy or sane? record attempt for the smallest boat to cross the Atlantic. Yachting Monthly. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.yachtingmonthly.com/cruising-life/crazy-or-sane-record-attempt-for-the-smallest-boat-to-cross-the-atlantic-86938

-

What is the Gulf Stream? Met Office. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/weather/oceans/what-is-the-gulf-stream